Film Review: A Clockwork Orange (1971)

The history of cinema is littered with controversies, but few films have provoked as much moral panic as Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971). While earlier scandals—like Ecstasy’s orgasmic sighs—revolved around sex, the cultural upheavals of the 1960s shifted taboos toward violence. By the 1970s, directors like Sam Peckinpah and Wes Craven were gleefully dismantling the remnants of Hays Code prudery, but Kubrick’s adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s dystopian novel transcended mere shock tactics. Though not the era’s bloodiest film (its body count pales next to The Wild Bunch), A Clockwork Orange became a lightning rod for debates about art, morality, and state control. Its enduring infamy lies not in gore, but in its unflinching interrogation of free will, authority, and the human capacity for cruelty—a work as philosophically disquieting as it is visually audacious.

Burgess’s 1962 novel, a linguistic tour de force blending Russian-inflected slang (“Nadsat”) with Swiftian satire, provided fertile ground for Kubrick’s coldly precise style. Set in a near-future Britain where youth gangs terrorise a decaying society, the film follows Alex DeLarge (Malcolm McDowell), a Beethoven-loving sociopath who leads his “droogs” in nightly sprees of “ultra-violence.” Kubrick condenses Burgess’s plot into a triptych of transgression, punishment, and manipulation. After a botled home invasion leaves the eccentric Cat Lady (Miriam Karlin) dead, Alex is betrayed by his gang and sentenced to 14 years. In prison, he volunteers for the Ludovico Technique, a state-sanctioned aversion therapy that conditions him to associate violence and sex with crippling nausea. The procedure’s unintended side effect—rendering Alex physically ill at the sound of Beethoven—becomes his undoing when he crosses paths with Frank Alexander (Patrick Magee), a writer whose wife he previously raped.

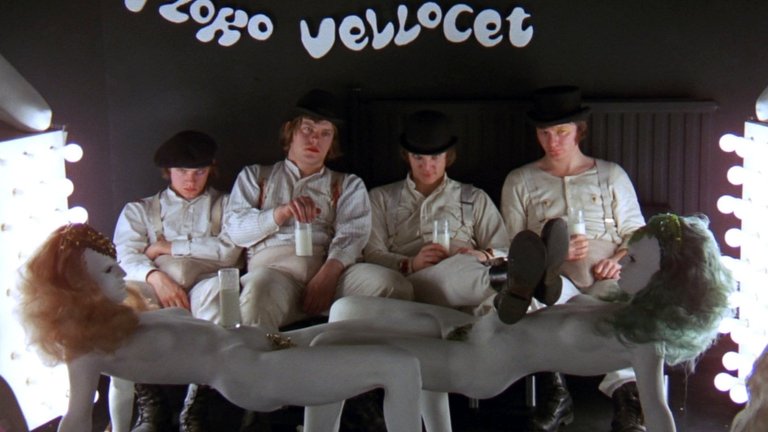

Kubrick’s Britain is a carnival of grotesques: neon-lit milk bars, Brutalist housing blocks, and a government that swaps jackboots for lab coats. The film’s aesthetic, a lurid blend of pop-art kink and clinical futurism, reflects the director’s fascination with societal rot. Production designer John Barry cloaks this dystopia in primary colours and surreal geometries—Alex’s eyeliner-clad stare framed against blood-red walls, the Ludovico lab’s sterile whiteness—creating a world both recognisable and alien.

If 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) embodied the techno-utopianism of the 1960s, A Clockwork Orange channels the 1970s’ creeping nihilism. The Moon landing’s afterglow had faded in the decade that would bring Watergate, oil crises, and urban decay. Kubrick, ever the misanthrope, frames Alex not as an outlier, but as a product of his environment. The film’s adults—lecherous probation officers, power-hungry ministers, vengeful intellectuals—are as morally bankrupt as the youth they fear. Even Alex’s droogs, now policemen, wield state-sanctioned brutality with the same glee they once reserved for random assaults.

This generational clash mirrors real-world anxieties. The post-war baby boomers, raised in relative prosperity, revolted against their parents’ values, embracing hedonism and anti-establishment rhetoric. Burgess and Kubrick skewer both sides: the youth’s amorality and the authorities’ hypocrisy. The Ludovico Technique, touted as a humane alternative to prisons, becomes a tool for thought control, reducing Alex to a “clockwork orange”—mechanically “good” but stripped of humanity.

At its core, A Clockwork Orange wrestles with a timeless question: is forced morality preferable to free-willed evil? The prison chaplain (Godfrey Quigley) condemns Ludovico as a violation of soul: “When a man cannot choose, he ceases to be a man.” Yet the film offers no easy answers. Alex’s pre-therapy savagery is horrifying—the infamous rape of Mrs. Alexander (Adrienne Corri), set to Gene Kelly’s Singin’ in the Rain, remains one of cinema’s most chilling sequences. His post-therapy helplessness, however, is equally grotesque. Kubrick refuses to sentimentalise either state, framing Alex as both victim and villain.

The political subtext is razor-sharp. The interior minister (Anthony Sharp), a smirking bureaucrat, exploits Alex’s conditioning for electoral gain, while Frank Alexander, the crippled writer, weaponises him against the state. Both sides dehumanise Alex, reducing him to a pawn in their power games. Kubrick’s Britain is a carousel of authoritarianism, where individual agency is crushed whether by gangs or governments.

Few sci-fi films age as gracefully as A Clockwork Orange. While its cassette tapes and typewriters date it to the 1970s, its vision of a society numbed by media and controlled by technocrats feels eerily prescient. The Korova Milk Bar, with its phallic sculptures and drugged beverages, prefigures today’s binge-drinking culture; the Ludovico screenings, where Alex is forced to watch violent propaganda, mirror modern debates about desensitisation through screens.

Burgess’s Nadsat slang, initially jarring, now seems prophetic of internet-age vernacular—a coded patois blending foreign loanwords and playful neologisms. McDowell’s delivery, alternately poetic and menacing, elevates the dialogue into a perverse liturgy.

Kubrick’s use of music is diabolically brilliant. Wendy Carlos’s Moog synthesiser adaptations of Beethoven and Rossini bridge the classical and the synthetic, mirroring Alex’s split psyche. The Ninth Symphony, a symbol of Enlightenment ideals, becomes a trigger for Pavlovian horror. Most audacious is Alex’s rendition of Singin’ in the Rain during the rape scene—a perversion of innocence that imbues the tune with lasting unease. The film’s closing credits, set to Gene Kelly’s original version, twist the knife: art’s beauty cannot sanitise its misuse.

The film’s production lore is riddled with “what-ifs.” The Rolling Stones once eyed the project, with Mick Jagger as Alex—a prospect that, given Jagger’s wooden performance in Performance (1970), would have been catastrophic. Instead, Kubrick cast Malcolm McDowell, then known for If.... (1968). McDowell’s Alex is a masterclass in charismatic depravity: his smirk, swagger, and Shakespearean soliloquies (“Oh my brothers…”) make him paradoxically magnetic. Yet the role typecast him; for years, Hollywood saw only the monster, not the actor.

The supporting cast shines equally. Patrick Magee’s Frank Alexander, a wheelchair-bound rage machine, and Adrienne Corri’s traumatised wife embody Burgess’s critique of intellectual hypocrisy. David Prowse, later Darth Vader, looms ominously as a bodyguard—a nod to the film’s influence on pop culture.

A Clockwork Orange’s release ignited firestorms. Feminists decried its sexual violence; conservatives branded it a manifesto for anarchy. Kubrick, harassed by death threats and tabloid fury, withdrew the film from UK cinemas in 1973—a ban upheld until his death in 1999. Ironically, this censorship cemented its cult status, with bootleg VHS tapes circulating like contraband.

Burgess, meanwhile, disowned Kubrick’s adaptation for omitting the novel’s final chapter, where Alex outgrows his violent phase. The director’s darker ending—Alex cured of Ludovico, grinning at the camera—suggests cyclical evil, a notion Burgess found nihilistic. Yet this very ambiguity fuels the film’s endurance.

Half a century later, A Clockwork Orange’s controversies seem quaint next to modern extremes like Saw or Euphoria. Violence, once taboo, is now mainstream—a development Kubrick arguably anticipated. What endures is the film’s philosophical heft and aesthetic daring. It is a work of contradictions: repulsive yet hypnotic, cynical yet deeply humanist. Alex, for all his monstrosity, remains a mirror to our capacity for cruelty and complicity. In an age of algorithm-driven conformity and performative outrage, A Clockwork Orange feels less like a period piece than a prophecy—a clockwork warning that still ticks.

RATING: 9/10 (++++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9

Muchas gracias

A Clockwork Orange is the epitome of "control". I often think of it when viewing society's actions and reactions to cult-like behavior instituted as "free will" today and marvel at the ease of acceptance.

Perhaps people should view the original movie if they haven't to see the plots playing out in this century. They will be shocked at the similarities.

I've loved Rodney's acting since I first saw him in the first Planet of the Apes.

Thanks for sharing.

!lady

You mistook Roddy McDowell for Malcolm McDowell. Understandable mistake, because last names are the same and Roddy spent all of The Planet of the Apes under heavy make-up.

So true. My mistake.