Film Review: Andrei Rublev (1966)

In recent years, it has become fashionable, at least for those who take word of Western mainstream media as gospel, to see Russia as the root of global strife. Yet Russians themselves, steeped in their nation’s complex history, are more inclined to trace their current challenges to a legacy of turmoil stretching back centuries. This tumult is vividly captured in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev, a 1966 Soviet biopic that, despite its own fraught journey through censorship and controversy, has ascended to become a cornerstone of Russian, Soviet, and world cinema. The film’s unflinching portrayal of medieval Russia’s chaos—its political fragmentation, foreign domination, and social decay—resonates with a timeless relevance, offering a mirror to the nation’s enduring struggles with power, faith, and artistic expression.

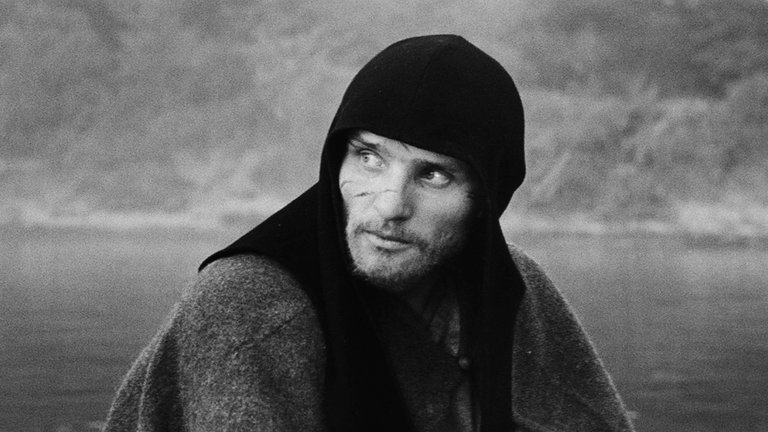

The protagonist, played by Anatoly Solonitsyn, is the historical figure of Andrei Rublev, an Orthodox monk and painter whose life remains shrouded in mystery. Little is known of his personal experiences, yet his artistic legacy endures through the luminous frescoes and icons that cemented his status as a paragon of 15th-century Russian art. His work, marked by a serene blend of spirituality and humanism, influenced generations of artists, and in 1988, the Russian Orthodox Church posthumously canonized him as a saint. Rublev’s life, as depicted in Tarkovsky’s film, becomes a vehicle for exploring the tensions between creativity and oppression, faith and doubt, and the artist’s role in a fractured world.

Rublev’s world was one of perpetual instability. Medieval Russia was a patchwork of feudal principalities, locked in internecine strife and subjected to the brutal tribute demands of the Mongol-Tatar overlords. This era, rife with violence and exploitation, left the peasantry in perpetual despair, their lives further ravaged by disease, famine, and the capricious whims of warlords. The screenplay, co-written by Tarkovsky and Andrei Konchalovsky, constructs a mosaic of vignettes spanning roughly a quarter-century of Rublev’s life. These episodes do not merely chronicle his biography but interrogate how the era’s brutality shaped his art and worldview.

The film opens with a prologue centred on Yefim, a visionary inventor (played by Nikolay Glazkov), whose ill-fated attempt to launch the world’s first balloon—a symbol of human aspiration—ends in tragic failure. This metaphor for idealism’s fragility sets the tone for Rublev’s journey. We are introduced to Rublev and his fellow monks, Daniel Chorny (Nikolai Grinko) and Kirill (Ivan Lapikov), who seek work painting churches. Rublev’s apprenticeship under the renowned Theophan the Greek (Nikolai Sergeyev) sparks jealousy among his peers, while political tensions between Moscow’s Grand Prince Vasily I and his brother Yuri of Zvenigorod (both played by Yuri Nazarin) escalate. Yuri’s alliance with the Tatar khan Edigu (Bolot Beyshenaliyev) culminates in the brutal sack of Vladimir, where Rublev’s church and artworks are destroyed. The massacre’s climax sees Rublev killing a soldier to save a vulnerable girl, Durochka (Irma Rausch), an act that traumatises him into silence and artistic withdrawal. Years later, Rublev’s faith in humanity is restored by Boriska (Nikolai Burlyayev), a teenage bellfounder whose perseverance in casting a monumental bell—a symbol of renewal—mirrors the resilience of the human spirit.

+Despite budget constraints, Andrei Rublev is a visual tour de force. Tarkovsky’s second film dwarfs his debut, Ivan’s Childhood, in scale and ambition, with meticulously reconstructed 15th-century settings and sweeping long takes that immerse viewers in the period’s textures. The black-and-white cinematography by Vadim Yusov lends the film an air of solemnity, situating it within the austere traditions of 1960s art-house cinema. Yet the film’s epic runtime—over three hours—belies its grandeur, evoking the weight of history itself. Unlike Hollywood’s glossy spectacles, Tarkovsky’s Russia is unvarnished, its beauty and horror equally unflinching.

The film’s graphic violence, however, is its most contentious feature. Scenes of torture, mutilation, and the grotesque killing of animals—such as cows set ablaze and a horse thrown from a tower—challenge viewers’ sensibilities. Notably, Tarkovsky’s use of a real horse in the latter scene, unconcerned with Western animal welfare standards, underscores his commitment to visceral authenticity. Even more unsettling is the pagan festival sequence, where nudity and implied sexual activity transgress Soviet-era modesty norms. These elements, while artistically justified, initially drew censors’ ire and alienated some audiences.

The film’s most incendiary critiques, however, target Soviet ideological dogma. Tarkovsky’s subtle condemnation of tyranny—whether Mongol oppression, feudal despotism, or the persecution of dissenters like the skomorokh (a jester figure, played by Roland Bykov)—echoes the stifling atmosphere of Brezhnev-era USSR. Rublev’s moral centre derives from his Christian faith, a direct affront to the state’s enforced atheism. The film’s most daring moment comes when persecuted pagans lament Christian oppression, mirroring Tarkovsky’s own resentment of Soviet repression of religion. This layering of historical and contemporary allegory transforms the film into a subversive act of resistance.

The cast delivers uniformly strong performances. Nikolai Burlyayev, a child actor from Ivan’s Childhood, imbues Boriska with a quiet determination that elevates his role beyond mere symbolism. Solonitsyn, then an unknown, anchors the film with his restrained portrayal of Rublev’s inner turmoil. Yet Tarkovsky’s direction occasionally falters. The film’s notorious pacing—marked by lengthy, meditative sequences—can test modern viewers’ patience, a flaw that would persist in his later works. Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov’s score, while functional, lacks the emotional depth needed to elevate key moments.

Upon completion, Andrei Rublev faced immediate backlash from Soviet authorities, who sought to suppress it for its unambiguous critique of authoritarianism and religious themes. A muted 1966 Moscow premiere and a truncated 1969 Cannes showing (where it won the FIPRESCI Prize) initially limited its impact. Only after sustained advocacy by artists and intellectuals was it finally released domestically in 1971. This delayed reception paradoxically amplified its mythos, cementing its status as a clandestine masterpiece.

Today, Andrei Rublev stands as a testament to cinema’s power to interrogate history and ideology. Its exploration of artistic integrity in oppressive contexts remains eerily prescient, while its technical brilliance and philosophical depth continue to inspire filmmakers and thinkers. The film’s refusal to romanticize the past—or to shy from its horrors—challenges viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about power, faith, and human resilience. In an era when Russia’s history is again weaponized in global discourse, Tarkovsky’s vision reminds us that understanding the past is not merely an academic exercise but a moral imperative.

RATING: 7/10 (+++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9

Posted Using INLEO