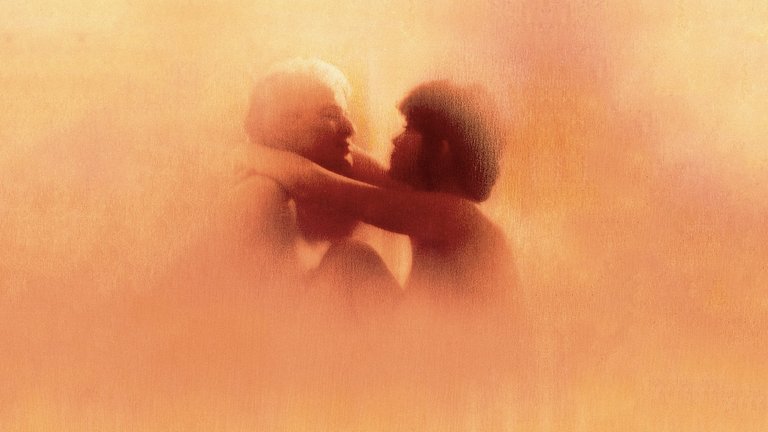

Film Review: Last Tango in Paris (1972)

The Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s reshaped the cultural landscape, and its echoes in cinema are often distilled into a handful of films that purportedly shattered taboos regarding onscreen sexuality. Titles such as Deep Throat (1972), with its infamous non-simulated sex scenes, became cultural shorthand for the era’s sexual experimentation, their notoriety cementing them in public memory. Yet, within months of Deep Throat’s release, another film emerged that would temporarily eclipse it as a benchmark for cinematic eroticism, only to be later re-evaluated as a relic of its time. Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris (1972), a Franco-Italian romantic drama, became entangled in controversy and moral panics across the globe. While it initially seemed to herald a new era of explicitness in mainstream cinema, it ultimately marked the end of an experimental phase rather than the dawn of a liberated cinematic frontier. Over half a century later, its legacy is one of artistic ambition, flawed execution, and a paradoxical blend of groundbreaking audacity and dated conventions.

The film’s protagonist, Jeanne (Maria Schneider), is a young woman dealing with the complexities of adulthood. Arriving in Parisian building to seek apartment, she encounters Paul (Marlon Brando), a middle-aged American expatriate who has inherited a dilapidated hotel from his late wife, Rosa, who recently died by suicide. Paul, haunted by grief, views the apartment Jeanne is renting as more than a residence—it is a neutral space for anonymous sexual encounters. Jeanne, the sheltered daughter of a military officer’s family, agrees to his proposition, embarking on a volatile affair defined solely by carnal desire. The pair deliberately withhold their names, symbolizing their transactional relationship. Meanwhile, Jeanne’s fiancé, Thomas (Jean-Pierre Léaud), an aspiring filmmaker, documents their relationship through a cinéma vérité documentary, adding a layer of meta-narrative tension. Paul’s fixation on Rosa’s memory—manifested in a haunting monologue addressed to her corpse—contrasts with his exploitation of Jeanne, whose own restlessness stems from her desire to escape the stifling bourgeois future Thomas represents. When Jeanne decides to end the affair, Paul’s refusal to accept her departure culminates in a violent, tragic climax that underscores the destructive undercurrents of their relationship.

Unlike Deep Throat, a film unapologetically rooted in pornography, Last Tango in Paris positioned itself within the mainstream, albeit within the arthouse tradition. Its reputation as a landmark of cinematic eroticism stemmed not from its explicit content alone, but from the moral outcry it provoked. In Italy, Bertolucci faced a criminal trial for “offending public morality,” and the film was banned for years in several countries, including Spain and Portugal. These controversies amplified its allure, framing it as a radical challenge to censorship. Yet, its arthouse pedigree distinguished it from exploitation cinema, situating it within a tradition of European art films that prioritized psychological depth over sensationalism.

Today, the film’s erotic reputation feels oddly anachronistic. Much of its supposed “shock value” derives not from sensuality but from its stark, unsettling aesthetic. The production design, influenced by the brooding, grotesque imagery of Francis Bacon’s paintings, transforms Parisian apartments into claustrophobic, shadowy spaces reminiscent of horror films. The recurring motif of blood in the bathtub where Rosa died casts a pall of dread over the narrative, while Paul’s conversation with his wife’s corpse—a scene rendered in solemn, almost ritualistic tones—feels more macabre than arousing. Even the famed sodomy scene, which involved butter as a lubricant, is devoid of eroticism, its discomfort amplified by Brando’s visceral performance and Schneider’s palpable unease. Similarly, the reciprocal act Paul demands of Jeanne lacks the titillation one might expect, instead evoking a transactional power dynamic that underscores the relationship’s toxicity.

The film’s power lies not in its explicit content but in its performances. Brando, nearing the zenith of his career (coincidentally, The Godfather was released the same year), delivers a masterclass in emotional intensity. His portrayal of Paul—a man oscillating between charm and desperation, ultimately reduced to a pitiable wreck—reveals layers of grief and self-loathing. Schneider, then 20 years old, brings a haunting vulnerability to Jeanne, whose childish impulsiveness clashes with her sexually mature body. Their chemistry is undeniable; their affair becomes a mutual escape, Paul from his guilt over Rosa’s death, Jeanne from the confines of her privileged but stifling upbringing. Their dynamic, both magnetic and repellent, drives the narrative’s emotional core.

Gato Barbieri’s jazz-infused score further elevates the film. The haunting, improvisational melodies underscore the characters’ inner turmoil, while the music’s crescendos and silences mirror the tension between desire and despair. This aural backdrop helps mitigate the film’s occasionally sluggish pacing, though its three-hour runtime strains credibility at points, particularly in secondary subplots involving Paul’s hotel and Thomas’s documentary.

Despite its commercial success fueled by controversy, Last Tango in Paris’s reign as a benchmark for cinematic eroticism was short-lived. Within years, films like Emmanuelle (1974), a straightforwardly explicit exploitation film starring Sylvia Kristel, overshadowed it, catering to audiences seeking unambiguous titillation. The rise of home video further marginalized theatrical erotic cinema, shifting the medium’s focus away from big-screen spectacle. The film’s reputation was further tarnished by Schneider’s later claims that she felt manipulated and abused during production, accusations that resonated with feminist critiques of the era’s portrayal of female sexuality. Her accounts painted Bertolucci as a manipulative director who exploited her youth, framing the film’s eroticism as a vehicle for male fantasy rather than mutual exploration. These revelations, along with its dated aesthetics, have cemented its status as a problematic artifact rather than a timeless classic.

Pauline Kael, the influential critic who championed the film as the vanguard of a new era of cinematic freedom, was ultimately proven wrong. The brief window when X-rated films (like Deep Throat or Last Tango) could attain mainstream acclaim closed swiftly. By the late 1970s, explicitly erotic content was relegated to niche arthouse circuits, and Last Tango in Paris became a relic of a moment when audacious sexuality and artistic pretension briefly converged.

In its original context, Last Tango in Paris was a provocative experiment, its controversies amplifying its cultural impact. Decades later, stripped of its shock value and historical baggage, it remains a flawed yet compelling work. Bertolucci’s direction is assured, Brando and Schneider’s performances are unforgettable, and the film’s exploration of grief, desire, and identity retains emotional resonance. While its erotic scenes now feel more unsettling than arousing, and its narrative pacing uneven, it endures as a testament to cinema’s capacity to grapple with human complexity—even when its ambitions exceed its execution. For cinephiles, it remains a fascinating artifact, a product of its time that continues to spark debate, if not outright admiration. In the pantheon of 1970s cinema, it occupies a peculiar niche: neither a straightforward masterpiece nor a mere curiosity, but a reminder that art and exploitation often walk a fine line—one that Last Tango in Paris straddled with all the ambiguity of its protagonists’ doomed affair.

RATING: 7/10 (+++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9

Gotta love a bit of butter and existential dread — it perfectly puts the 70s cinema in a nutshell. Weird how the film was hailed as revolutionary now just feels… kinda messed up.