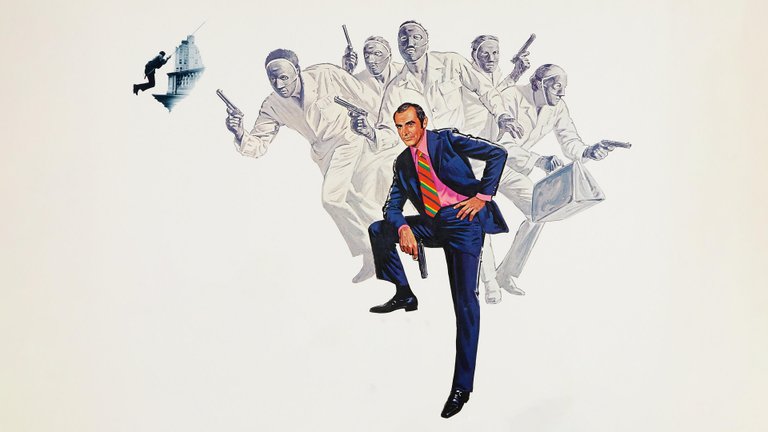

Film Review: The Anderson Tapes (1971)

Some films endure not for their artistic brilliance but for their novelty, capturing fleeting moments of cultural or cinematic transition. The Anderson Tapes, Sidney Lumet’s 1971 crime thriller, falls squarely into this category. A product of Hollywood’s post-Hays Code era, the film is notable for its early use of surveillance as both a narrative device and thematic preoccupation. Yet, despite its technical ingenuity, it fails to resonate as a memorable experience for general audiences. Lumet, a director whose résumé spans classics like 12 Angry Men and Dog Day Afternoon, here delivers a film that is more intriguing as a historical artifact than as a compelling story. Its status as one of the first major Hollywood films to explore the omnipresent gaze of surveillance—long before The Conversation—ensures its niche appeal, but its uneven execution leaves it stranded between ambition and mediocrity.

Based on Lawrence Sanders’ 1970 Edgar Award-winning novel of the same name, The Anderson Tapes adapts a narrative constructed entirely from fictional wiretap transcripts, police reports, and surveillance footage. The book’s fragmented, documentary-like style presented a challenge for adaptation, and Lumet’s film largely replicates this structure through a mosaic of cameras and recording devices, overlapping dialogue, and visual cues hinting at unseen observers. Critics at the time were underwhelmed, with many noting the film’s cold, procedural tone. Decades later, the appraisal remains largely unchanged: The Anderson Tapes is admired for its concept but dismissed as a derivative heist film lacking emotional resonance.

The film follows John “Duke” Anderson (Sean Connery), a charming, unrepentant safe cracker released after a decade in prison. Reconnecting with Ingrid Everleigh (Dyan Cannon), an old girlfriend living as “kept woman” of rich businessman , Duke becomes fixated on her opulent Manhattan apartment building—a symbol of the excess he craves. His plan to orchestrate a simultaneous robbery of all apartments is ambitious, requiring a crew of specialists: a flamboyant gay antique dealer (Martin Balsam), an elderly ex-con longing for prison (Stanley Adams), and a tech-savvy electronics expert (Christopher Walken in his breakout role). To fund the operation, Duke seeks backing from mob boss Pat Angelo (Alan King), who insists the crew include Rocco “Socks” Parelli (Val Avery), a violent thug destined to be killed to eliminate loose ends.

The twist? Every angle of the heist is monitored by government agencies—FBI, Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, and IRS—whose surveillance systems fail spectacularly. Despite the building being saturated with cameras and listening devices, the agencies’ bureaucratic inertia ensures they miss the crime until it’s too late. Duke’s crew proceeds to take hostages and ransack apartments, only for a single misstep—not checking paraplegic boy’s room and thus missing his ham radio—to alert police. The film’s climax is less a nail-biting showdown than a farcical unraveling, with the criminals fleeing as agencies scramble to cover their incompetence. The final scene reveals that the surveillance tapes, meant to expose the plot, are destroyed to protect institutional reputations—a darkly comic indictment of systemic ineptitude.

The Anderson Tapes underperformed at the box office but achieved modest returns, buoyed by Connery’s star power and the then-booming heist genre. Critics, however, were lukewarm. This ambivalence persists today: while praised for its technical ambition, the film is often relegated to niche discussions about surveillance cinema or Lumet’s filmography. Its legacy is that of a “so bad it’s good” curiosity rather than a critical darling.

Connery’s involvement was central to the film’s commercial prospects. By 1971, he was seeking roles beyond James Bond, and Duke Anderson—a suave, calculating criminal with a penchant for introspection—seemed an ideal vehicle. Yet his performance is subdued, leaning into the actor’s charisma without offering much depth. The role’s “lovable rogue” persona, though fitting the heist genre’s anti-establishment ethos, feels generic. The post-Hays Code era allowed for morally ambiguous protagonists to escape punishment, a theme The Anderson Tapes teases but ultimately walks from. Frank Pierson’s screenplay (later Oscar-winning for Cool Hand Luke) toys with the possibility of the gang’s escape, only to undercut it with a clumsily executed downfall.

The film’s appeal to 1970s audiences lay in its defiance of old Hollywood norms: the criminals are clever, the system is corrupt, and the stakes feel real. Yet Connery’s restrained delivery—compared to his fiery Bond persona—leaves the film feeling emotionally distant, a flaw compounded by Lumet’s lack of visual flair.

While Connery is serviceable, the film’s true strengths lie in its supporting players. Alan King’s Pat Angelo is a hoot, a mob boss whose eccentricity borders on whimsy, while Balsam’s antique dealer—campy, witty, and entirely self-serving—steals scenes with his flamboyance. Walken, in his first major role, exudes a quiet intensity that hints at his future stardom, though his character’s tech expertise is underutilised. The real disappointment is Dyan Cannon’s Ingrid, whose role reduces her to a plot device and romantic interest. Rumours of an off-screen affair between Connery and Cannon added tabloid intrigue but little narrative substance. Lumet’s direction fails to elevate these characters beyond their paper-thin motivations, leaving the film’s ensemble feeling like a parade of clichés.

The film’s most audacious choice is its mimicking of Sanders’ novelistic structure, using surveillance footage and bureaucratic reports to frame the narrative. Lumet employs overlapping audio, and subtle visual cues to evoke a panopticon-like atmosphere. The irony is biting: the very systems meant to protect society become instruments of incompetence. The surveillance apparatus—so pervasive it borders on absurd—is rendered impotent by red tape and institutional laziness. The final destruction of the tapes underscores the farcical nature of authority.

Had The Anderson Tapes been released post-Watergate (1972), its critique of governmental overreach and secrecy might have resonated more deeply. Instead, it feels ahead of its time in conception but tonally mismatched in execution. The surveillance motif, while innovative, is undercut by the film’s dry tone, making its dystopian undercurrents feel more like a punchline than a warning.

Sidney Lumet’s direction is workmanlike but uninspired. The heist sequence, interspersed with flash-forwards showing police investigators dissecting the aftermath, is confusingly paced. Lumet’s reliance on static shots and stilted dialogue undermines tension. The film’s fragmented structure, meant to mirror the novel’s style, instead creates narrative dissonance, leaving viewers unsure whether to focus on the criminals’ antics or the bureaucratic bumbling.

The climax, which should be a crescendo of chaos, plays out like a poorly staged play. Lumet’s inability to balance suspense with the film’s meta-commentary results in a finale that feels anticlimactic. The director’s signature social realist style—effective in films like Serpico—here feels mismatched with the material’s absurdist undertones.

The Anderson Tapes is a fascinating curio of 1970s cinema, a film that attempted to marry surveillance satire with heist thrills but stumbled over its own ambition. Its innovations—particularly its early exploration of pervasive surveillance—ensure its place in cinematic history, but its execution leaves much to be desired. While it may intrigue film students or devotees of transitional cinema, The Anderson Tapes ultimately proves that even with a bold premise and star power, a film can be as ineffectual as the surveillance systems it mocks.

RATING: 6/10 (++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9