Film Review: Three (Tri, 1965)

Yugoslav cinema is predominantly recognised for two significant trends: the country-specific genre of Partisan films and the Yugoslav Black Wave, a film movement that reached its peak in the late 1960s and early 1970s. These two cinematic currents converged in the 1965 film Three, directed by Aleksandar “Saša” Petrović. This film not only exemplifies the thematic concerns of its time but also showcases the stylistic innovations characteristic of the Black Wave, making it a vital piece of Yugoslav film history.

Three is adapted from Fern and Fire, a collection of stories published in 1962 by Serbian author Antonije Isaković. The narratives within this collection are partially inspired by Isaković's own experiences as a Yugoslav Partisan during World War II. Isaković is credited as co-author of screenplay, together with Petrović.

The structure of Three is anthology-based, comprising three distinct yet interconnected stories that revolve around the protagonist, Miloš Bojanić, portrayed by Velimir “Bata” Živojinović.

The first story unfolds at the onset of World War II in April 1941, shortly after Nazi Germany and its Axis allies invaded the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Here, Miloš finds himself amidst a crowd at a railway station in Serbia, anxiously awaiting a train that promises safety. The atmosphere is thick with paranoia and mistrust, exacerbated by the apparent collapse of the Royal Yugoslav Army and the swift advance of German forces, explained with apparently omnipresent “fifth column”. A photographer (played by Slobodan Perović) at the station, who wears a beret and has a speech impediment mistaken for a German accent, becomes a victim of this hysteria. Despite his desperate protests that he is merely a refugee waiting for his family, he is executed by gendarmes. The tragic irony deepens when his wife (played by Vesna Krajina) arrives to corroborate his innocence—yet it is too late for him.

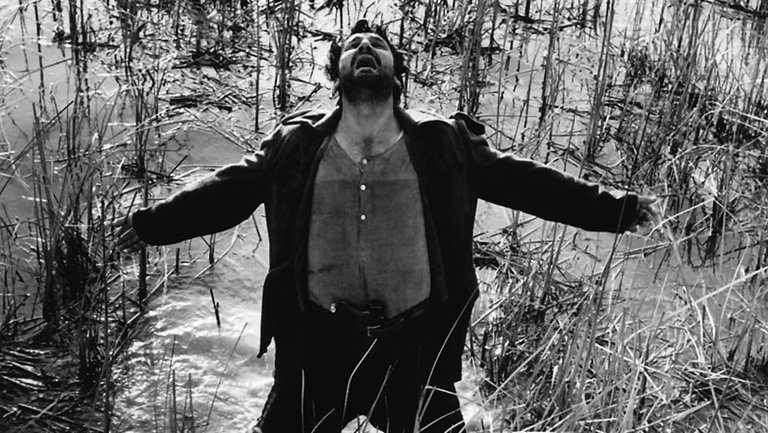

In contrast, the second story takes place two years later on mountainous terrain near the Adriatic Coast. Miloš has now become a Partisan fighter who has survived an encirclement by German SS troops. As he strives for safety while being relentlessly pursued, he encounters another survivor nicknamed Žabac (“The Frog”, played by Vojislav Mirić). Their camaraderie offers a fleeting sense of hope amid chaos; however, their fate takes a grim turn when they are surrounded by enemy forces in a swamp. Understanding that their chances for survival would improve if they separated, Žabac heroically sacrifices himself to allow Miloš to escape—a poignant moment that underscores the brutal realities of war.

The final segment occurs as World War II nears its conclusion in Serbia, now liberated by victorious Partisans. Miloš has ascended to the rank of high-ranking officer. He shares an improvised office with a colleague from OZNA, the newly established secret police, tasked with interrogating prisoners—Nazi officers and collaborators likely facing execution post-interrogation. Among these captives is an attractive young woman (played by Senka Veletanlić) who captures Miloš's interest; however, his hopes are dashed when he learns she is confirmed as a Gestapo agent. This revelation forces Miloš into moral conflict as he grapples with his feelings towards her amidst the harsh realities of justice in post-war Yugoslavia.

Three stands out as one of the more memorable Yugoslav films from its era despite its brief running time and black-and-white cinematography crafted by Tomislav Pinter. Critics have praised its triptych structure; each story not only connects through Miloš but also explores themes surrounding death in war—depicting it as often absurd and arbitrary. Despite his sympathies for those around him, Miloš remains powerless to prevent these tragic outcomes.

The film is particularly noteworthy for its stylistic choices that echo those found in Black Wave classics—featuring rural settings and low-class characters amid an atmosphere steeped in bleakness. This tone is in the first time occasionally lightened through moments of black humour or cheerful Gypsy music that starkly contrasts with the tragic conclusion of the segment.

The second segment aligns most closely with traditional Partisan films; it includes action sequences where Miloš occasionally kills pursuing enemies—echoing portrayals typical of Bata Živojinović’s roles as Rambo-like supermen in other classics of the genre. However, unlike those archetypal heroes, this protagonist appears unkempt and dressed in rags rather than military garb. His emotional breakdown upon learning about Žabac’s fate marks a departure from glorified heroism towards portraying Partisans as flawed human beings—a revolutionary perspective for Yugoslav cinema at that time.

Perhaps the darkest and most subversive aspect arises in the final segment where Miloš’s discomfort with how the new regime handles its adversaries becomes evident. Despite having every reason to feel triumphant following liberation, he struggles with moral ambiguity regarding executions carried out under the new order. The film subtly suggests there may be little distinction between Partisans/Communists and those who had previously persecuted them.

While this critique of recent history may seem mild compared to more radical Black Wave films produced shortly thereafter, Three must have appeared extraordinary to Western audiences expecting typical regime propaganda from Yugoslavia. Created during an era when Yugoslavia was experimenting with economic and political reforms, Three benefited from increased creative freedom for its filmmakers—resulting in a film that remains strikingly memorable.

However, Three is not without its imperfections; some segments feel slightly prolonged, particularly the first story where the character played by Stole Aranđelović—a religious fanatic—seems overly exaggerated within the narrative context. Despite these shortcomings, Three garnered critical acclaim; it shared the prestigious Golden Arena at the Pula Film Festival with Vatroslav Mimica’s Prometheus from the Island and was later nominated as Yugoslavia's official entry for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

Aleksandar Petrović continued to achieve success internationally following Three, winning accolades such as the Grand Prix at Cannes Film Festival for his subsequent work I Even Met Happy Gypsies.

Three remains an essential film within both Yugoslav cinema and broader discussions about war narratives—offering profound insights into human nature amidst conflict while challenging established cinematic conventions of heroism and morality.

RATING: 8/10 (+++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9

Posted Using INLEO