Film Review: The War Lord (1965)

Popular misconceptions about the Middle Ages often veer towards two extremes. On one hand, the period is frequently depicted as a bleak expanse of bigotry, poverty, backwardness, and violence, a so-called "Dark Age" where humanity languished in ignorance. On the other, it is romanticised as a golden age of moral certainty, where Christian faith provided a moral compass, common folk lived in harmony with nature, and those in power adhered to the lofty ideals of chivalry and honour. The latter view, in particular, has been perpetuated by Hollywood, especially in the grandiose historical epics of the 1950s. However, by the 1960s, as cultural attitudes began to shift across the board, so too did the portrayal of the medieval period in cinema. This change is evident in The War Lord, a 1965 film directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, which attempts to present a more nuanced and gritty depiction of the Middle Ages, albeit with mixed results.

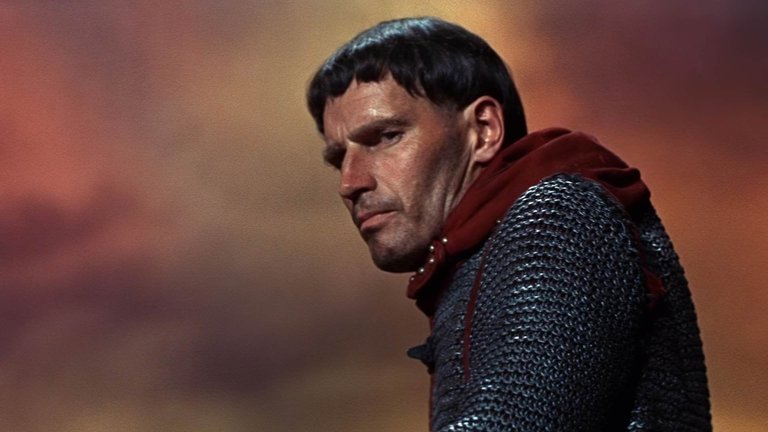

Based on Leslie Stevens’ 1956 Broadway play The Lovers, The War Lord transplants its story to 11th-century Normandy, under the rule of the fictional Duke of William of Ghent. The film follows Chrysagon de la Cruex (played by Charlton Heston), a trusted knight sent to oversee a remote, swampy outpost plagued by Frisian raids. Accompanied by his retinue, including his brother Draco (played by Guy Stockwell) and loyal lieutenant Bors (played by Richard Boone), Chrysagon arrives just in time to repel a Frisian attack led by a prince (played by Henry Wilcoxon) and capture the prince’s young son. The knight becomes fascinated by the local villagers, who, despite the presence of a Catholic priest (played by Maurice Evans), still practice pagan rituals. Chrysagon’s interest soon turns to obsession when he becomes infatuated with Bronwyn (played by Rosemary Forsyth), the beautiful adopted daughter of village elder Odins (played by Niall MacGinnis), who is betrothed to Odins’ son Marc (played by James Farentino). Encouraged by Draco, Chrysagon invokes the feudal privilege of ius primae noctis—spending the first night with the bride. However, after a night of passion, Chrysagon refuses to release Bronwyn, sparking outrage among the villagers. This act of hubris leads to a rebellion, with the villagers aiding the Frisians in their assault on Chrysagon’s tower.

For Charlton Heston, The War Lord was a passion project. By the mid-1960s, Heston had become synonymous with larger-than-life historical figures, having starred in epics such as Ben-Hur and El Cid. With this film, he sought to distance himself from his heroic image, opting instead to portray a more flawed and morally ambiguous character. However, in doing so, Heston may have gone too far in the opposite direction. Chrysagon is not merely a jaded and cynical warrior; he is a man consumed by lust and a blatant disregard for the well-being of others, whether his retinue or the serfs under his protection. His invocation of ius primae noctis and subsequent refusal to release Bronwyn can only be described as an act of rape, a far cry from the noble heroes Heston had previously embodied. This stark departure from his established persona likely contributed to the film’s lacklustre box office performance.

Yet, despite its attempts to subvert traditional heroic tropes, The War Lord stops short of fully committing to its darker themes. The screenplay, penned by John Collier and Millard Kaufman, significantly alters the grim ending of Stevens’ original play, opting for a more redemptive conclusion. Chrysagon, after recognising the error of his ways, attempts to atone for his actions through noble gestures and envisions a new life with Bronwyn, who, somewhat implausibly, develops feelings for her captor. This shift undermines the film’s potential as a bold critique of feudal power dynamics and leaves the audience with a resolution that feels both contrived and unsatisfying.

Where the script falters, however, Franklin Schaffner’s direction excels. Schaffner, who would later helm iconic films such as Planet of the Apes, demonstrates his skill by seamlessly blending melodrama with action. The battle scenes, though small in scale, are executed with a realism that sets them apart from the grandiose set pieces of earlier medieval epics. The siege of Chrysagon’s tower, in particular, is both thrilling and grounded, showcasing Schaffner’s ability to create tension within a confined setting. The film’s attention to historical detail is also commendable. From authentic costumes and props to the nuanced portrayal of the coexistence of Christianity and paganism, The War Lord offers a more accurate depiction of medieval life than many of its contemporaries. The film’s portrayal of feudal society—marked by a stark division between the noble elite and the serfs—is equally well-realised, even if the concept of ius primae noctis is now widely regarded as a myth rather than historical fact.

Schaffner’s vision is further enhanced by the film’s production design and musical score. Despite its modest budget, The War Lord convincingly recreates 11th-century Normandy on California locations, with the isolated village and tower serving as effective backdrops for the story’s intimate drama. Jerome Moross’ evocative score adds to the period atmosphere, with the main theme achieving popularity as an instrumental cover by The Shadows.

However, the film is not without its flaws, particularly in its casting. While Rosemary Forsyth is undeniably striking and embodies the ethereal beauty that drives Chrysagon to obsession, her performance lacks chemistry with Heston. Bronwyn is a frustratingly passive character, and Forsyth’s portrayal does little to elevate her beyond a mere plot device. Guy Stockwell, as Chrysagon’s increasingly resentful brother Draco, delivers a standout performance, but Richard Boone feels miscast as Bors, lacking the gravitas the role demands. James Farentino, as the aggrieved Marc, is similarly underutilised, his performance failing to convey the depth of his character’s anger and betrayal.

Despite its shortcomings, The War Lord remains an intriguing and ambitious film. While it may not have achieved the commercial or critical success Heston had hoped for, it stands as a noteworthy attempt to challenge the romanticised portrayal of the Middle Ages prevalent in Hollywood cinema. Its blend of historical authenticity, moral complexity, and Schaffner’s deft direction make it a compelling watch, even for those not typically drawn to revisionist takes on history. Though flawed, The War Lord is a film that deserves recognition for its willingness to grapple with the darker aspects of its subject matter, offering a glimpse into a medieval world that is far removed from the chivalric fantasies of old.

RATING: 5/10 (++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9

Posted Using INLEO

Old movies have a very special character. They are very distinctive in all their details, but for me, the acting cannot be repeated.